Volterra is one of the most attractive of all the Tuscan walled towns -- amazingly preserved. The town is about a thousand years old and the buildings we see today easily date back to the Middle Ages, and the earliest foundations of Volterra go back to the Etruscan days, nearly 3000 years ago.

There was an Etruscan town here, one of the main dozen Etruscan towns in what is today Tuscany, and eventually was conquered by ancient Rome. That was about 300 BC and the Romans ruled from that era until about 500 A.D. and then comes the Middle Ages, and later occupation by Florence. Back in the Middle Ages and the early Renaissance, 1400s, there was a lot of rivalry between the city states, and Volterra was actually an autonomous city, state.

It has a marvelous wall around it, which is beautifully preserved today. It goes for about 3 miles all around the city, preserving the stone historical gem intact. It's mostly pedestrian zone when you're in the old town.

The residents live in the old town and they all work here. It's a great tourist center, and yet it's a little bit off the beaten track of tourists. You can't get here by train. You can get here by bus, so it's so for example about a two-hour bus ride away from Florence – direct buses maybe five times a day. So it's certainly feasible if you are staying in Florence for a couple of days or in Siena, you can get over the Volterra, and you would really be delighted to see how beautiful this town is.

Of course there are a whole bunch of restaurants, there's pizzerias, snack shops, coffee shops, lots of little stores.

There's a handful of very charming small hotels within the walls of Volterra in the old town. We stayed at one called La Locanda, quite nice, and there are three or four other significant hotels and then some tiny ones and some bed-and-breakfasts, pensiones, so you can find places to stay. If you are here during the busy season, of course, you want to be sure to make reservations.

We are here in the off-season of November, which is really a lovely time to be traveling in Italy. Temperatures are nice and there are very few tourists around. Most attractions are open, some are closed, some restaurants are closed, and attractions to have somewhat limited hours, but November is wonderful to be here. The availability of hotel rooms is no problem. You can get a table in a good restaurant without worrying, and you don't see many crowds. You have the town all to yourself, shared with the locals.

We'll be taking a look at Volterra with a local guide, Annie Adair, who is quite famous in the area as one of the premier local tour guides in Volterra, and Annie is going to be showing us the town. Annie is now an Italian citizen as well as an American citizen. She has been living in Volterra for 23 years, though originally from Washington DC. She fell in love with Volterra quite unexpectedly traveling here after graduating from college.

Her website is www.tuscantour.com

Annie’s commentary follows.

Volterra is Tuscany's oldest continuously inhabited town. That’s why it’s such a great place for history lovers, but it's also, it’s also a town that has a very vibrant local community. It’s not a big town, it’s not a big city, it’s more than a village. But it's just, it's got so much going for it today as it did in past centuries.

Volterra is a town that has many important museums and monuments, but one of the things that I love most about this town is the fact that it's filled with lanes and alleys, and residential homes, and hidden corners.

I think it took me several months actually to discover all of them when I first moved to Volterra and somethings that that my friends and family and visitors often remark on as well is finding their own favorite secret corner, hidden lane in Volterra, having a glass of wine watching the sunset and seeing the little old ladies walked by with their shopping bags, and the mothers with strollers, and those poorly behaved Italian children, probably one of them was my own, wreaking havoc as they run down the lanes. It's real life – it's a community – it's Volterra's heart and soul.

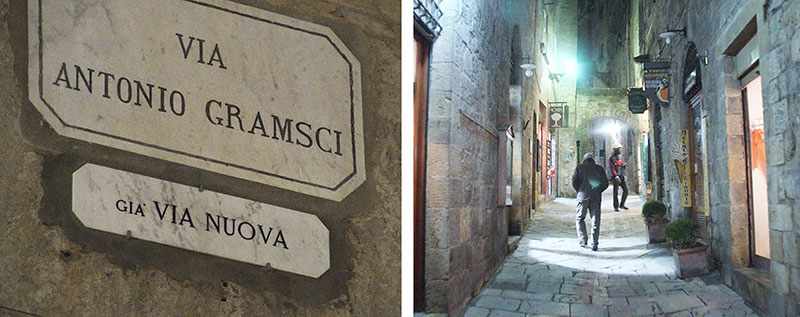

One of the main intersections of Volterra is where Via Matteoti and Via Gramsci meet. This is often where Voltans will come and run into their friends and decide to have a cocktail. Via Mateotti is where some of the Volterran's favorite cafés and restaurants, and little shoe stores, and various pizza by the slice places are to be found. Now, what are the daily rituals? After going to the butcher and the baker, and I'm not sure we have a candlestick maker, but, you know getting all your daily provisions, Volterrans often come out on the city streets around 6:30-7:00 PM and have the evening passeggiata.

So, what that means, too, is you don't ever have to make an appointment with your friends to say we'll meet on Thursday evening at 6. You go out, have your passeggiata and you'll most likely run into them. It's a wonderful way of keeping the community alive.

Also, Volterra has something special about it that even larger towns like Siena don't have, and that's the fact that numerous bars and cafés in town open from the morning pastries through lunch in the afternoon are also open after dinner.

So many Volterrans continue that habit of the passeggiata also after dinner, coming out and you'll see 90-year-old men, two-year-old children, 30-somethings, 20-year-old singles, all together in the same café having a chamomile tea, a glass of wine, a Bacardi breezer, whatever it may be. And the community stays in touch that way. So it's wonderful when you're part of the local community but it's also wonderful when you're visiting the town as well, to be a part of that.

The locals in Tuscany often have their own names for each street, so if you look at a map you'll see one name, but if you ask a local for directions you will be told another so what they often do is you have the big sign with the proper map name that is on the map, and then underneath it a little sign that says "Gia" which means previously known as what everybody is actually calling it.

Volterra's population is officially 12,000 people. Now that is a very vague town area, so it includes a large rural area. But about half of the population lives inside the city walls, which today have a perimeter of about 4 km or 2.5 miles, and half live outside the city walls.

But most of the people who live outside the city walls, and in many other towns and villages, gather in Volterra and use it for their services, their shopping. Volterra actually is a hub for many services and also for education. We have six high schools in Volterra, serving not just the 12,000 people within the jurisdiction of Volterra but also many other areas, towns in the rural area.

The seasons in which Volterra is most, not crowded, but most-visited let's say, are spring and summer without a doubt. So, from April through to June – June is a particularly busy month, and of May, June. The summer months actually are not that busy at all. July, August. You have a lot of Italians traveling and visiting, but not so many foreign visitors. And then September, October, it actually is quite busy again, and things will start to get slower again November, though personally my favorite time to be here is November.

Not only is the town filled with local folk and that's enough to keep the town vibrant, but also, chestnuts are being harvested, the new wine is being produced, the olives are picked and pressed, the community presses into new oil. Truffles and wild mushrooms are being found. If someone were to ask me when you get Volterra at its most real, and that's I would say November.

Volterra has been inhabited since at least 1500 BC, that time when central Italy was inhabited by a people called the Villanovans. Later in the eighth century BC, they would be more or less replaced by the slightly more famous Etruscans. Now the Etruscans and Tuscans are not the same thing, but Tuscany doesn't get its name from these ancient inhabitants of the region. They were pre-Romans, although they do kind of develop together with Rome, but they're doing some of the world's most magnificent gold jewelry. Not to mention many other cultural productions at a time when Romulus and Remus were basically being suckled by the she-wolf on the banks of the Tiber River.

Volterra would become one the, one of the 12 Etruscan city-states and one of the most powerful and populous. By the fourth century BC, Etruscan Volterra counted a population of about 20,000 people, which is astonishing, I mean it’s larger than Rome for almost a century. And it also means that Volterra in the Etruscan period had a lot more people in it than it does today. So today, we’re officially 12,000 people, but that counts people like me who live in the countryside, whereas in centuries past, they’d only count the people living inside the city walls, about 6000, compared to 20,000 back in the fourth century BC.

Volterra’s main square is called Piazza dei Priori, the center of civic life, since as long as anyone can remember. The oldest building in the square is the Tower of the Piglet, the Tore del Porcellino. We don’t know exactly when it was built, but we know when it was constructed it was originally used as a residence for a private noble family, like so many of the house towers built in Tuscan towns in that period.

The most important building in the square and the second oldest is called the Palazzo dei Priori, the Priors Palace. It was constructed between 1209 and 1257, and it has a very important claim to fame, and that is that it's the oldest and the first building constructed for a city-state in Europe. The architect of the Florence town hall, Arnolfo di Camdio, actually stated in his preparatory notes that he intended Florence' s town hall to be a larger and more grandiose version of the Palazzo dei Priori in Volterra.

The name, Priors Palace, tells us that the title given to the first rulers of the city-states, they were called priors and they ruled with an oligarchy, and by no means was this pure democracy, but the city-states really did represent an important first step towards democracy in Europe.

San Gimignano, Volterra, Florence, and Pisa all had house towers such as this. What we do know is that in 1226, halfway through the construction of the town hall building, the Palazzo dei Priori, the town government was so fed up with waiting for the construction to finish, that they bought the tower from the family had previously owned it. And it's in that tower that would hold their government meetings, until of course their palace was completed.

Because it was no longer just the Holy Roman Empire or the Pope aand far off lands calling the shots. Now there was greater self and local rule. The prior and his family would live inside the building you see. It's where the town Council would meet. It's where governance was was done, but also it was a private residence. The prior would be sequestered inside the building for the entire duration of his term. The terms had to be short and because this was a term of suffering, suffering, and it was usually 6 to 12 months. During that period the prior was never allowed to leave the building.

Of course, he had advisors to be his intermediaries with the outside world so he could actually govern, but that the concern was corruption, bribery, conflict of interest. Of course we surpassed all of this concerns today. But they kept him inside the building, and they would never leave him out, and would never let him leave, and would never let anyone else in to try to avoid that corruption. But of course, this man is a Christian. He may not be allied with the Pope, but he is still of course a Christian. So how is he to continue his religious life jf he can't leave the building? And they are not to leave, but the priests go up, either. Well, the compromise was found by building the Palazzo dei Priori back-to-back with the Cathedral.

The black and white striping that you see is actually the backside of Volterra's Cathedral, consecrated in 1120 by Pope Callistus II. and there's a wing of the Town Hall building on the opposite side that actually goes on top of the Cathedral, so that from within prior' s quarters he can open wooden shutters and have a clear view straight down onto the altar of the Cathedral. So from there he could kneel on a pew and attend mass, and many people would say, also keep a very tight control on everything that was being said and done inside.

Volterra' s Cathedral was consecrated by Pope Callistus II in 1120. It's built in a very humble version of one of Europe's most magnificent architectural styles, the Pisan Romanesque, which will be one of the most important foundation stones to Renaissance architecture. The Cathedral that we see today built at some time before 1120, is not the first, but the third version of the Cathedral here in Volterra. You can see with the black and white striping that this is a holy building, and unlike the other yellow stone buildings in the rest of the square, all of which are civic buildings.

Volterra was actually one of the first diocese in Christianity to ever be established, in terms of its geographic limits. Volterra is the birthplace of five popes, and the first of these five popes was quite an influential figure. He was Peter's successor; his name was Linus. Not much is known about him, but it's widely believed that he gave Volterra such prominence within the early Christian church. And that would remain for many centuries.

On the façade of the Cathedral you can find some interesting details and including the Carolingian floral motif along the cornices and also the wreath of pagan Roman stones in the main portal, the main most important entrance into this most important Christian building in town. In fact, the white marble columns and capitals that you see on this main portal came from Volterra's Roman theater, already in disuse for hundreds of years. They thought why not take these beautiful white stones and use them for the Cathedral. But it was also more than that. It was almost as if they were we reclaiming their pagan past as something that Christianity had conquered and was building upon.

We're here in Piazza San Giovanni, which is the religious square of Volterra. It holds a Baptistery which was built in 1285 in the Pisan Romanesque style, which is the same style used for the Pisa Baptistery as well, which was constructed 1153. Other baptisteries in Tuscany will often have this bi-chrome striping and similar styles. It's essential to have a Baptistery if you have a Cathedral because wherever you have a seat of the diocese, one bishop, one Cathedral, one Baptistery. Because in this period it was very important for their religious beliefs that you enter the Cathedral as a Christian. Thus the need for a separate building. But also remember that Christianity hadn't really been establish throughout Europe as the common religion for that many centuries, and so it was all the more important to give something monumental for those who are entering into the Christian faith, to make it a ceremonious occasion with such a magnificent building.

Now the Baptistery here in Volterra is octagonal. Almost all baptisteries are octagonal, although some are circular. This too has significance because both the circle and figure-8 are endless figures. They have no beginning or end point – symbols of the infinity and thus of the eternal life gained through baptism in the Christian faith.

Now the fact that we have in this religious square four buildings that marked for important moments in the life of a Christian was no coincidence. Now in Volterra, like any other Italian town, wherever you have the seat of the diocese, you have Cathedral, Baptistery, hospital and cemetery. Now we know longer have a functioning hospital here – it moved out in the 1980s to larger buildings outside of town.

And also, the cemetery is long gone, because they realized that the new Christian practice of burying the dead inside the city walls was not the hottest idea, especially when plagued with headings, contagion would spread like wildfire, but originally these four buildings signified the cycle of life: birth, with a baptistery; life, in the Cathedral; difficulty and need, in the hospital; and of course, death, the cemetery. That's to remind man of his Vanitas, of his vanity. Or more precisely what they mean is, what are you left with in the end, because there is an end, because this is the natural cycle of life. In the end you have bones, you have a soul, but you don't have your possessions, you don't have your appearance, don't have the power you been trying to amass. All of those will be in vain, vanitas. And so the corollary is, of course, what they are after is, care for your soul during your lifetime because that's what will be of importance. But the conundrum is, artistically, how do you represent the soul? No one has ever come up with a commonly recognized way of representing the human soul.

And so, what they often will do is show us bones instead, because that's the other thing you our left with. So, an example this, you can actually see on the façade of the little Chapel of the Misericordia, where you have a skull and V-shaped wings. They show you the bones to remind you, man, care for your soul and the wings, there in the shape of the V to represent the V of vanity of Vanitas.

The Misericordia is the volunteer ambulance association. They are volunteers. The full name is actually “Arciconfraternita della Misericordia”, so it's a fraternity of compassion. That's a very old-fashioned name, but understandable considering the Association first appeared in Tuscany in 1348. That's the year Tuscans will never forget, because that's when the Black Death, or the bubonic plague, ravaged the area. When between five months, May to October in one year, between 1/2 to 2/3 of the people you knew died. Well, the Misericordia are the courageous men, most of them the deliverymen of the towns who volunteered to move the sick and dead outside the city walls, otherwise they feared everyone might die. Well it's been around ever since, and it's an association that actually still unique, just to Tuscany.

One of their specialties here is alabaster, and earlier they had a lot of alabaster mines which are actually still in operation today. And the shops sell this very fine thin white stone alabaster, and they make plates out of it and bowls, lampshades, little figurines.

Earlier in the history of Volterra a different mineral was important. It was alum that was used for setting the die in textiles. That was very important in Florence, which was a great textile center and one of the reasons why Florence under the Medici wanted to control Volterra, and so they did, they conquered it. Lorenzo the Magnificent sent the Duke of Urbino over here with his troops and massacred some civilians in Volterra and subdued them, and then paid them a little pittance as a reward to keep them in line and for several hundred years, Florence dominated Volterra.

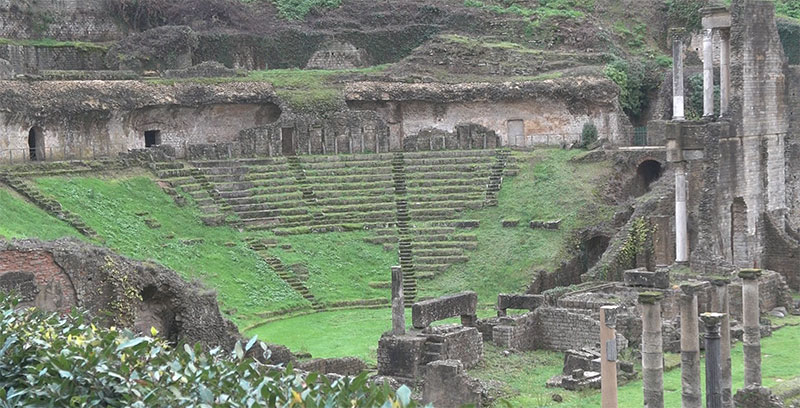

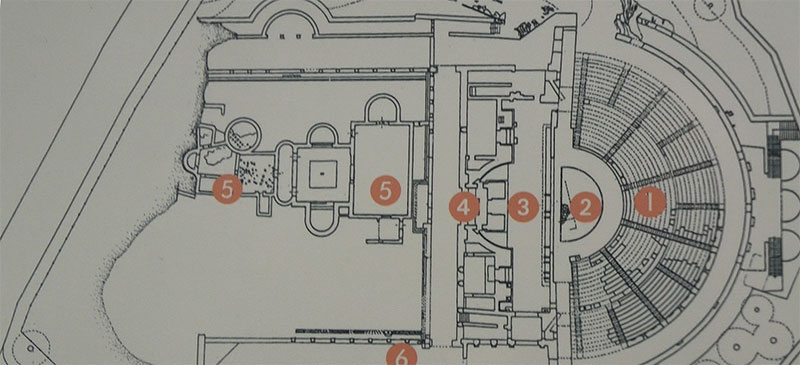

Volterra's Roman theater was constructed in the second half of the first century BC, dedicated to the reigning emperor, Augustus. And it's important also to note that we're not looking at an amphitheater, but a theater. Now, today we use amphitheater lot for outdoor arenas, but in ancient Rome there were theaters and there were amphitheaters, and they were different things. A theater was always a half-circle, a theater was always used for plays, and the theater was the most common form and place of entertainment throughout the Roman Republic. Only in the first century A.D. will you start to see amphitheaters – am-phi-theaters, double theaters. So, the form is different now. It's a circle or, more commonly even, an oval and it's used for lots of different types of entertainment, but mostly blood and cuts entertainment. It will come to pass that people will think, why would you want to go see a boring Roman re-adaptation of a Greek tragedy when you could go watch a guy bash another guy' s brains in? And so, theaters will get abandoned. That's why it's so rare and so special to have this theater still remaining here in Volterra. The theater had a seating capacity of about 2500 spectators.

The wealthy and noble, the patricians sat closer down to stage. The average Joe's farther up, just like today I suppose. When you get to the bottom of that sloped half-circle, there is a flat half-circle. And that was called the orchestra section. That's where the guest of honor would sit, so people like the Emperor Augustus. Augustus seems to have liked this theater of Vallebona here in Volterra, considering acoustics to be the best in the Empire, and also one of the most beautiful theaters as well.

This theater is also remarkable because it was the second-ever Roman theater built in stone. It's not out of a lack of resources or interest, but it was actually against the law in ancient Rome to build stone theaters. These Senate passed a law saying we welcome donations and we recognize that patrician families are are almost always donating theaters to their city, but we don't want them making grandiose permanent constructions as donations. So, theaters, yes continue donating to them, please, but make them wooden temporary structures. And so it would be for centuries, until they find a loophole, and that loophole to point to another Roman law that says wherever you have a temple dedicated to Rome's Capitoline triad, you have to have stone stairs leading to the temple, to correctly honor and distinguish those, the most important gods of Rome.

At the top of the cavea, the seating section, they put in three semicircular niches. Into those niches went a white marble statue of Juno, one of Jove and one of Minerva, and there you have your temple. What lay beneath aren't stone bleacher seats for the theater, but stairs leading to the temple, doing their duty as good Roman citizens honoring their gods. They get away with it in Volterra, that's when the rest of the Empire will realize they too can it, and so after this you will see a flood of constructionism of Roman theaters in stone.

On the back side of the theater are Volterra's third set of public baths, probably built at the end of the third century A.D. But they never used them at the same time. And we know that because the baths are constructed taking stones away from the theater. So for whatever reason, they had already abandoned the theater.

What we see are just the foundations of what were originally sumptuous rooms, with mosaic floors and probably marble inlay on the interior walls. Moving from the theater back towards the road would've been first, the vestibulum, the changing room, followed by the frigidarium, with cold water, then, very small, little oval tepidarium, with warm water, then the caldarium, with the hot water.

And then off to the right, a circular structure called the laconicum. Now, it was a sauna, and it was so hot in there, of course you couldn't help but laconically lounge and enjoy this spa-like experience. The Roman baths were so important to Roman culture. It was actually your right as Roman citizen to access them. This is a great service to keeping people happy and healthy.

But also, I think it's important to remember, loyal, because this is what your state provides for you. Anyone except a slave could go to these places, do exercises in the grassy outdoor area. Jump into the cold, the warm, the hot water bath. And also hydrate the skin with olive oil that would be provided free of charge and scrubbed clean with pumice sand. It's something that I think many people would like to have as a right today, myself included.

Porta e Fonte di Docciola. One can access the “fonte” through a stairway of 251 steps built in 1933 that the locals still call “via delle scalette di Docciola.” Two stone pointed arches built in the first half of the 13th century support the roof of the wash house with the “fonte”, a sort of rustic fountain of water.

So after the fall of the Roman Empire, it'll take a few hundred years of disuse in this area, and people start to realize, no one's going to fix it up again. So they start to use it as a salvage yard. They will take the columns, the capitals, to build the Cathedral and many other buildings in town. And then in the 13th century, new walls are built to surround and protect Volterra. It's a time of great fear, uncertainty. The walls were actually made tighter around Volterra, making the city smaller. Those are the walls that we see above the theater today. So, with the creation of these walls in the 13th century, the theaters and baths were no longer in the city center, but now outside the city walls.

The town then decides, well isn't this a convenient place to have all the local people dump their garbage instead of dumping your buckets of waste in the city streets, please take them dump them over the wall. So garbage piled up on top of theater and baths. A hill formed.

By the 1800s it was pretty clear that no one remembered ancient ruins being beneath the hill. By the 1900s it was also being used as a soccer field. Then you're using it as a donkey racetrack. And only in 1950, after World War II, did a local intellectual get a hunch that the theater may have been here. He will succeed in convincing the Italian state to give him a permit to do the dig, but he can't convince them to give him financing not in these postwar years. So he gets creative and finds a group of volunteers.

They did a massive operation of land movement and they did their job technically very well. That may be a surprise if you know that t facade hey were not archaeologists, not even the man behind the dig, Enrico Fiumi, was an archaeologist. He was very good at it, but he made a living by managing the finances of Volterra's psychiatric institute. It was a 6000-patient-large psychiatric institute, the 2nd largest hall for Italy's mentally ill. And that's where he found his volunteers. So we had psychiatric patients for 10 years excavate everything that we see today, and a happy side of the story is that most of the men involved in the dig were actually deemed healed throughout the process, and freed from institutional life. But I'm told that every single one of them, to a man, stayed on to see the completion of the dig.

Ah well, you know I could go on and on, but...

Google map of Volterra landmarks.