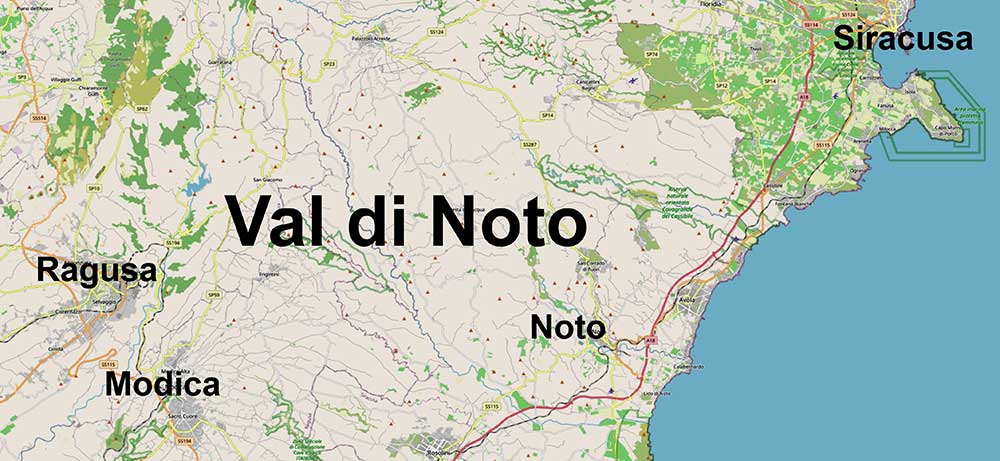

The Val di Noto occupies the southeastern corner of Sicily, where a group of towns underwent simultaneous reconstruction following the catastrophic earthquake of January 1693. The seismic event destroyed numerous settlements across the region, killing tens of thousands and leaving populations without shelter or infrastructure. Rather than rebuilding on damaged sites, planners and architects designed entirely new urban centers according to baroque principles that emphasized geometric order, wide streets, and integrated architectural programs. The reconstruction effort extended over several decades during the eighteenth century, creating a concentration of baroque architecture that UNESCO recognized collectively as a World Heritage Site in 2002.

Noto, Ragusa, and Modica represent three principal examples of this reconstruction after the earthquake of 1693, each demonstrating different approaches to baroque urban planning shaped by their distinct topographical settings. Noto occupies a plateau site where architects established a rational grid plan organized along an east-west axis, producing uniform streetscapes and interconnected plazas that exemplify theoretical baroque urbanism. Ragusa divides between two separate districts positioned on adjacent hills separated by a deep valley, with Ragusa Ibla maintaining baroque character while Ragusa Superiore developed as a modern administrative center. Modica extends through a steep valley where buildings rise vertically up hillsides and streets adapt to challenging terrain, creating a baroque townscape integrated with existing topography rather than imposed upon a cleared site.

.jpg)

The three towns share architectural vocabulary including carved stone facades, elaborate balconies supported by grotesque figures, monumental church fronts approached by dramatic staircases, and aristocratic palaces displaying sculptural decoration. This consistency reflects the work of architects including Rosario Gagliardi and Vincenzo Sinatra who practiced throughout the region, as well as shared building traditions among craftsmen who executed the decorative programs. The towns remain connected by regional roads that permit day trips between sites, allowing visitors to compare different manifestations of baroque reconstruction within a geographically concentrated area.

2up.jpg)

Noto is the easiest to reach from Siracusa as a day trip, one hour away by bus. It occupies a limestone plateau in southeastern Sicily, where the town's honey-colored buildings reflect light across the Asinaro Valley below. After the earthquake of 1693 destroyed the medieval settlement located several kilometers away, planners constructed an entirely new city according to baroque principles, creating one of the most coherent examples of eighteenth-century urban design in Europe. The reconstruction positioned religious, civic, and aristocratic architecture along a central east-west axis, establishing the corso as the primary thoroughfare that continues to organize daily life three centuries later.

The Main Thoroughfare: Corso Vittorio Emanuele

The historic center extends approximately one kilometer from Porta Reale at the western entrance to Piazza Mazzini at the eastern boundary. Corso Vittorio Emanuele traverses this distance as a pedestrian street, connecting three major plazas and forming the spine of the urban plan. Stone facades line both sides of the corso, their uniform height and consistent architectural vocabulary creating a continuous streetscape punctuated by church fronts and palace portals. Ground-floor spaces accommodate shops, cafes, and gelaterias that draw both visitors and residents throughout the day and into evening hours when the passeggiata fills the street with pedestrians.

.jpg)

The Central Axis and Principal Plazas

Piazza XVI Maggio serves as the entrance plaza where Via Ducezio meets the historic center. The Fontana d'Ercole anchors the space with its sculptural representation of Hercules, providing a focal point around which cafes with outdoor seating extend onto the pavement. The Porta Reale gateway marks the ceremonial threshold, constructed in 1838 with neoclassical elements including columns and symbolic sculptures representing civic virtues. Beyond this arch, the corso begins its progression through the baroque district.

Piazza del Municipio constitutes the ceremonial heart of Noto, where the Cattedrale di San Nicolò rises above a broad staircase that elevates the church facade several meters above street level. The cathedral dominates the urban landscape with three levels of columns and ornate decorative elements, its current form the result of reconstruction following the dome collapse of 1996. The interior preserves gilded altars and frescoed ceilings, while the structure serves as the focal point for religious processions and civic gatherings. Opposite the cathedral, Palazzo Ducezio houses the town hall in a neoclassical building designed by Vincenzo Sinatra in 1746 and completed in 1830. The palace interior features a reception hall with gold stuccoes and mirrors, and visitors who pay the three-euro entry fee can access the rooftop for views across the plaza toward the cathedral dome.

2up.jpg)

The Basilica del Santissimo Salvatore occupies a position adjacent to the cathedral as part of the former Benedictine convent complex, one of the largest sacred buildings in the city. The Monastero del Santissimo Salvatore extends across entire urban blocks, its enclosed gardens and courtyards now serving cultural and educational purposes while maintaining the architectural character of eighteenth-century monastic life. The Chiesa del SS. Salvatore features a concave facade and interior decorations that include baroque stuccoes, with adjacent terraces offering vantage points over the central plazas.

Via Nicolaci and the Aristocratic Quarter

Via Nicolaci ascends perpendicular to the corso, creating a sloped street lined with baroque palaces that terminates at the Chiesa di Montevergine at the upper end. The street achieves its greatest prominence during the Infiorata festival each May, when artists cover the entire pavement with elaborate designs created from flower petals. Throughout the year, the architectural density and uniform baroque character make this one of the most photographed streets in the city.

2up.jpg)

Palazzo Nicolaci di Villadorata stands as the principal aristocratic residence along Via Nicolaci, constructed in 1731 for the Nicolaci family who derived wealth from tuna fishing operations. The facade displays bulging wrought-iron balconies supported by carved stone figures including lions, sphinxes, mermaids, and grotesque creatures that demonstrate the sculptural ambition of baroque craftsmen. The interior contains ninety rooms with frescoed ceilings and eighteenth-century paintings, accessible to visitors for a four-euro entry fee that permits viewing of period furnishings and architectural details. The palace illustrates how noble families competed for visual prominence through increasingly elaborate facades and decorative elements.

Palazzo Impellizzeri and Palazzo Trigona represent additional aristocratic residences along Via Nicolaci, their carved balconies and decorative stonework contributing to the architectural ensemble. These buildings remain in private use, demonstrating how historic structures continue to serve residential functions while maintaining their contribution to the streetscape visible from public spaces. The Chiesa di San Carlo Borromeo occupies the elevated position at the street's terminus, its large portal with four columns and gargoyles creating an architectural focal point. The attached bell tower, over three centuries old, permits an eighty-step climb for two euros and fifty cents, providing panoramic views across the rooftops and plazas of the historic district.

Secondary Streets and Neighborhood Areas

Via Cavour runs parallel to Corso Vittorio Emanuele as a secondary thoroughfare lined with shops, artisan boutiques, and cafes. The street maintains less crowded conditions than the main corso while preserving the baroque architectural vocabulary in residential-scale buildings. Local businesses including bakeries and small shops serve residents who live in the historic center, demonstrating how the urban plan accommodated both ceremonial spaces and everyday functional requirements.

Quartiere Agliastrello constitutes one of Noto's oldest districts, characterized by narrow lanes, original stone houses, and residential ambiance that contrasts with the monumental architecture along the corso. The district offers insight into the layered history of settlement patterns and building types that existed before and after the earthquake reconstruction. Side streets including Vicolo Ventura feature arches and worn limestone steps suitable for observing local daily life away from tourist concentrations.

Via Rocco Pirri provides an alternative route connecting residential areas with the commercial district while maintaining baroque architectural character at a less monumental scale. Neighborhood services operate along the street, serving residents who occupy apartments in the historic center. The thoroughfare demonstrates the integration of functional spaces within the overall baroque planning system.

Public Spaces and Infrastructure

Giardino Pubblico provides green space adjacent to the historic center, with paths lined by mature trees, benches, and plantings that offer relief from stone-paved streets. The garden includes monuments and provides views toward the surrounding landscape, functioning as a gathering place during hot weather and a recreational area where families bring children. The site demonstrates nineteenth-century additions to the urban fabric that complemented the earlier baroque planning principles.

The covered market operates near the historic center, providing a venue where local residents purchase fresh produce, fish, meat, and other food products. The market displays regional agricultural products and demonstrates continuing traditional practices of food distribution, offering insight into daily life and local culinary culture beyond the restaurants serving tourists.

2up.jpg)

Teatro Comunale Tina Di Lorenzo occupies a baroque building along the corso, maintaining an ornate interior with multiple levels of boxes and decorative plasterwork following traditional Italian theater design. The venue hosts performances and cultural events while serving as an architectural landmark that reflects the cultural aspirations of the reconstruction period. The theater demonstrates how civic buildings complemented religious and aristocratic architecture in the baroque urban plan.

Religious Architecture Throughout the Center

Chiesa di Santa Chiara occupies a prominent location along Corso Vittorio Emanuele, its eighteenth-century construction displaying an oval interior with stucco decorations, cherubs, and twelve columns. The church connects to a cloistered convent and provides access to a rooftop terrace offering views toward the cathedral and across the town skyline. Visitors use the church steps as a vantage point for observing pedestrian traffic along the corso.

Chiesa di San Francesco all'Immacolata stands on an elevated platform reached by a broad staircase, creating a theatrical approach that mirrors the cathedral's presentation nearby. The facade incorporates baroque curves and decorative stonework, while the interior preserves altarpieces and religious artworks from the reconstruction period. The adjacent monastery buildings now serve cultural functions while maintaining their historic architectural character.

Chiesa di San Domenico displays a curved baroque front that creates a dynamic relationship with the adjacent street space through convex and concave surfaces. The building serves an active parish and maintains original interior decorations including altars and religious paintings. The structure represents one of several religious complexes that established the architectural character of the reconstructed city.

Chiesa del Santissimo Crocifisso occupies a location outside the most concentrated tourist area, containing significant artworks including a marble Madonna attributed to Francesco Laurana from the fifteenth century. This sculpture survived the earthquake and was salvaged from the original medieval city, representing pre-earthquake artistic heritage incorporated into the new baroque settlement. The church attracts visitors interested in earlier artistic periods and provides contrast to the dominant eighteenth-century aesthetic.

.jpg)

Noto historic center map

This interactive Google My Map shows locations of attractions with information that can be displayed by clicking on the symbols. It has a sidebar index and displays best in full-frame by clicking the box in top-right. You are welcome to make a copy as described here.

Practical Considerations for Visitors

Caffè Sicilia on the corso has gained recognition for traditional Sicilian pastries and gelato, attracting both tourists and residents to its outdoor seating area. The establishment functions as a social gathering point where people conduct conversations and observe pedestrian traffic along the main street, representing the commercial vitality that sustains the historic center beyond architectural tourism.

The passeggiata occurs during evening hours when residents walk in groups along the corso, stopping to converse while visitors occupy cafe seating areas. This social ritual provides insight into contemporary use of the historic center and demonstrates continuity of public life patterns that baroque planners anticipated when designing the wide pedestrian thoroughfare and interconnected plazas.

Organized day trips from Noto typically include nearby baroque towns including Ragusa and Modica, which share architectural heritage from the post-earthquake reconstruction period. These excursions permit comparison of different approaches to baroque urban planning while remaining within the southeastern region of Sicily. Transportation options include guided coach tours that cover multiple towns in a single day or self-directed visits using regional bus services that connect the provincial centers.

The city of Ragusa divides into an upper modern section and a lower baroque district known as Ibla, connected by staircases and roads. The upper part, Ragusa Superiore, centers around the Cathedral of San Giovanni Battista, a structure rebuilt in the eighteenth century after an earthquake, featuring a facade with columns and statues, and an interior with chapels and artworks. This cathedral overlooks Piazza San Giovanni, a square with surrounding buildings housing shops and cafes, serving as a gathering spot. Corso Italia runs as the main street in this area, lined with commercial establishments, including clothing stores and eateries, suitable for pedestrian strolling. The Museo Archeologico Ibleo occupies a building nearby, displaying artifacts from prehistoric to Roman periods excavated in the region. Ponte Vecchio spans a gorge, providing a walkway with views of the valley below and the lower town.

.jpg)

The staircase of Santa Maria delle Scale links the upper and lower sections, consisting of steps descending through residential zones, offering intermittent views of baroque rooftops and the surrounding countryside. Along this path, the Church of Santa Maria delle Scale stands midway, with a gothic portal salvaged from an earlier structure and baroque additions, including frescoes inside. The lower district, Ragusa Ibla, clusters around narrow streets and plazas rebuilt in baroque style. Duomo di San Giorgio dominates the area, positioned at the end of Piazza Duomo, accessed by a staircase, with a facade incorporating columns and a bell tower, and an interior containing altars and paintings. Piazza Duomo features outdoor seating from adjacent restaurants and acts as a social hub. Via Capitano Bocchieri and other lanes branch off, with historic palaces like Palazzo Arezzo di Trifiletti, open for tours showing frescoed rooms and furnishings.

.jpg)

Giardino Ibleo occupies the eastern edge of Ibla, a public garden with paths, palm trees, and benches overlooking the Irminio Valley. It includes ruins of ancient churches and provides a space for relaxation with panoramic sights of the landscape. The Circolo di Conversazione, a nineteenth-century social club in a palace, maintains period interiors visible from the exterior. The Church of San Giuseppe, in Piazza Pola, displays a concave facade and stucco decorations inside. Via Orfanotrofio serves as a shopping street with artisan workshops and chocolate shops, reflecting local crafts. The area around Largo Camerina offers views across the gorge to the upper town. Outlying areas include the Castello di Donnafugata, several kilometers away, a nineteenth-century residence with gardens and rooms open to visitors, surrounded by parkland.

2up.jpg)

Modica spreads across hillsides, divided into lower and upper sections connected by staircases and winding roads. The lower part, Modica Bassa, centers on Corso Umberto I, the primary thoroughfare lined with historic buildings, churches, and shops. This street serves as a pedestrian zone with commercial activity, including chocolate producers and cafes where visitors sample local products derived from Aztec methods introduced in the sixteenth century. The Chocolate Museum of Modica occupies a space along the corso, exhibiting tools and history related to chocolate production in the area. Chiesa di San Pietro stands nearby, an eighteenth-century church reached by steps flanked by apostle statues, with a facade featuring columns and an interior of stucco work and frescoes. Piazza Matteotti adjoins, providing an open space with surrounding facades.

2up.jpg)

Side streets off the corso lead to residential zones, such as Via Grimaldi, with artisan boutiques and eateries. The Palazzo della Cultura houses a museum with archaeological finds from the region. A bridge over the dried riverbed connects parts of the lower town, offering views of layered architecture climbing the slopes. The staircase to Modica Alta ascends from the lower area, consisting of steps passing baroque facades and providing elevated sights of the town below. Midway, viewpoints allow observation of the urban layout and distant hills.

2up.jpg)

In the upper section, Modica Alta, Duomo di San Giorgio crowns the hill, accessed by a long staircase from below, with a facade of curves and columns, and an interior including chapels and artworks. This church overlooks the surrounding districts and serves as a landmark visible from multiple points. Piazza San Giorgio fronts it, a small square used for gatherings. Nearby, the Castello dei Conti, remnants of a medieval fortress, provide a belvedere with panoramic views over the rooftops, valleys, and sea in the distance. Via Castello winds through this area, with historic houses and occasional gardens. The Church of Santa Maria del Gesù, slightly offset, features gothic elements preserved from earlier construction. Outlying areas include the Mulino ad Acqua, a water mill museum several kilometers away, demonstrating traditional grain processing with operational machinery. The Cava d'Ispica, a nearby gorge, contains archaeological sites with rock dwellings and trails for walking amid natural scenery.

.jpg)

Exploring Val di Noto: Organized Day Tours Versus Public Buses

In the Val di Noto, organized day tours and public buses offer distinct approaches to navigating Noto, Ragusa, and Modica. Organized tours, often via air-conditioned coaches or minibuses from Catania or Syracuse, provide structured itineraries covering baroque highlights like Noto's Corso Vittorio Emanuele and Ragusa Ibla. Guides deliver historical context on earthquake reconstructions, with pick-up/drop-off convenience and group meals included, typically lasting 8-10 hours for €50-€100 per person. These tours suit first-timers, minimizing logistics amid winding roads, though they follow fixed schedules and crowd sites.

Public buses, operated by AST or SAIS, connect towns affordably—€5-€10 one-way—but run infrequently, with unreliable online timetables requiring local station checks. From Siracusa, a bus to Noto takes about 60 minutes; Ragusa-Modica links demand early starts, making it difficult to see all three in one day. This option allows flexible pacing, yet demands advance planning and tolerance for delays or sparse routes. For seamless exploration, organized tours excel in efficiency; buses foster independence at lower cost.